Flat Affect

I’m a fan of British crime dramas. They usually follow a predictable format. There’s a detective who is a crime-solving savant that is respected but seen as weird and prone to sudden insights. They often jump out of their chair and run down the hall in the middle of a conversation. The sidekick, usually a subordinate one or two rungs lower on the organizational hierarchy, is fiercely loyal to the detective and goes along with the unorthodox crime-solving strategies even when they know it will only lead to trouble. And there’s always a benevolent, often frustrated supervising senior officer who tolerates the detective’s antics because it leads to a better closed case rate. It’s the kind of show that you watch while you’re doing something else like grading papers or paying bills because you can maintain the gist of what’s going on without paying attention to every detail.

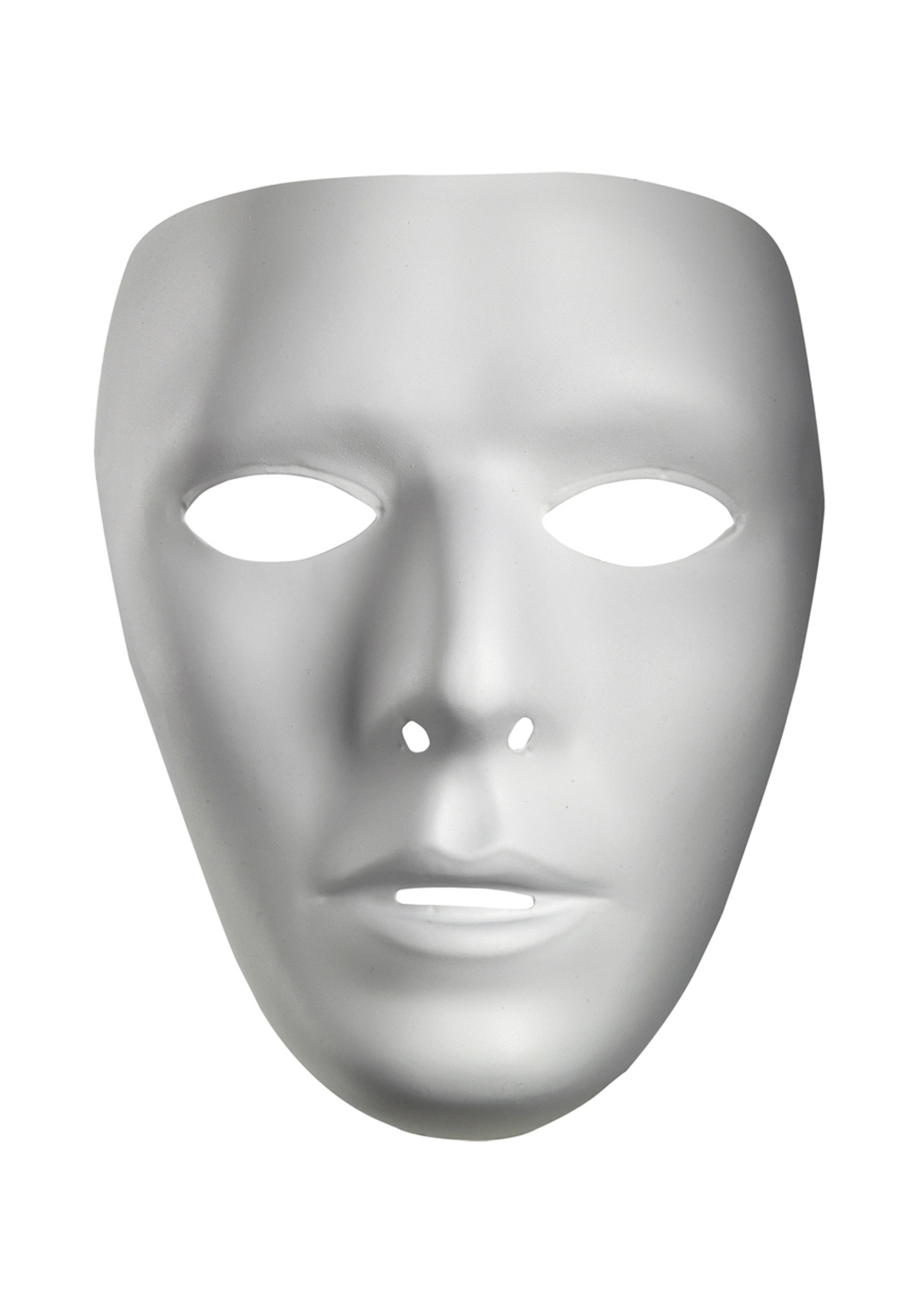

The other day I started watching a series I hadn’t seen before. The character that is supposed to be the crime-solving savant seems to have only one facial expression. Whether she’s standing in a blood-spattered room, brainstorming with her sidekick, or standing up to the benevolent superior, the detective’s unchanging expression gives the impression that she’s deciding between a latte or cappuccino at Starbucks. Medical professionals call it flat affect and it is associated with mental illness. Not saying that the actor is mentally ill, it’s more likely she’s just not a very good actor. It wasn’t until the third episode that I realized her savant skills are characterized by three gestures; cupping her chin in her hand, tapping her fingertips against her temples, and scratching the back of her head. By the fifth episode, the director started using a montage of clues from previous scenes to help the viewer understand that the detective was about to have a burst of insight and pull together clues that everyone else missed. That got me thinking about characterization and the ways writers show the character’s personality.

The detective’s monotone facial expression reminded me of books that I haven’t able to finish because the characters are flat and boring. The actions and dialogue aren’t enough to make them dimensional. The author has to step in and explain so the reader knows what’s going on, much like the director of the TV show started using a montage to help the viewer recognize when the detective was having an ‘aha’ moment. Those little bits of explanation pull me out of the story. It’s a little like when you’re listening to one of your friends describe something that happened, and their spouse keeps interrupting to add to what they’re saying. Extremely annoying, right?

When I look at my own work, the characters that seem fully developed are the ones that I’ve written by pretending that I am them. Getting inside the character’s head is essential. When I feel a character going flat or when I’m working with a new character, I interview the character. What are their hopes and dreams? What holds them back? What’s their biggest fear? What was their childhood like? What’s their family like? What’s their favorite color, food, song? I have a conversation with them – usually in my head but sometimes out loud. The other thing that seems to work for me is acting out the scene as much as I can or drawing on my own past, similar experience. Someone in the story dies, I remember what it was like when I lost someone I love. Someone in the story is terrified, I remember the times in my life when I’ve been terrified. I want my characters to be so fully developed that the reader doesn’t think they’re made out of cardboard.

The monotone expression crime-solving savant character also gave me a new appreciation for my playwright and screenwriter friends. It must be horrible to put your heart and soul into a script only to have the part given to someone who can’t bring the character to life.